Hello and welcome back! This is the first installment of a new series I’m starting, dedicated to all things print—magazines, books, and more. My goal is to spotlight publications, dive deep into what makes them culturally significant, their art direction, explore their design contributions, and examine their lasting impact.

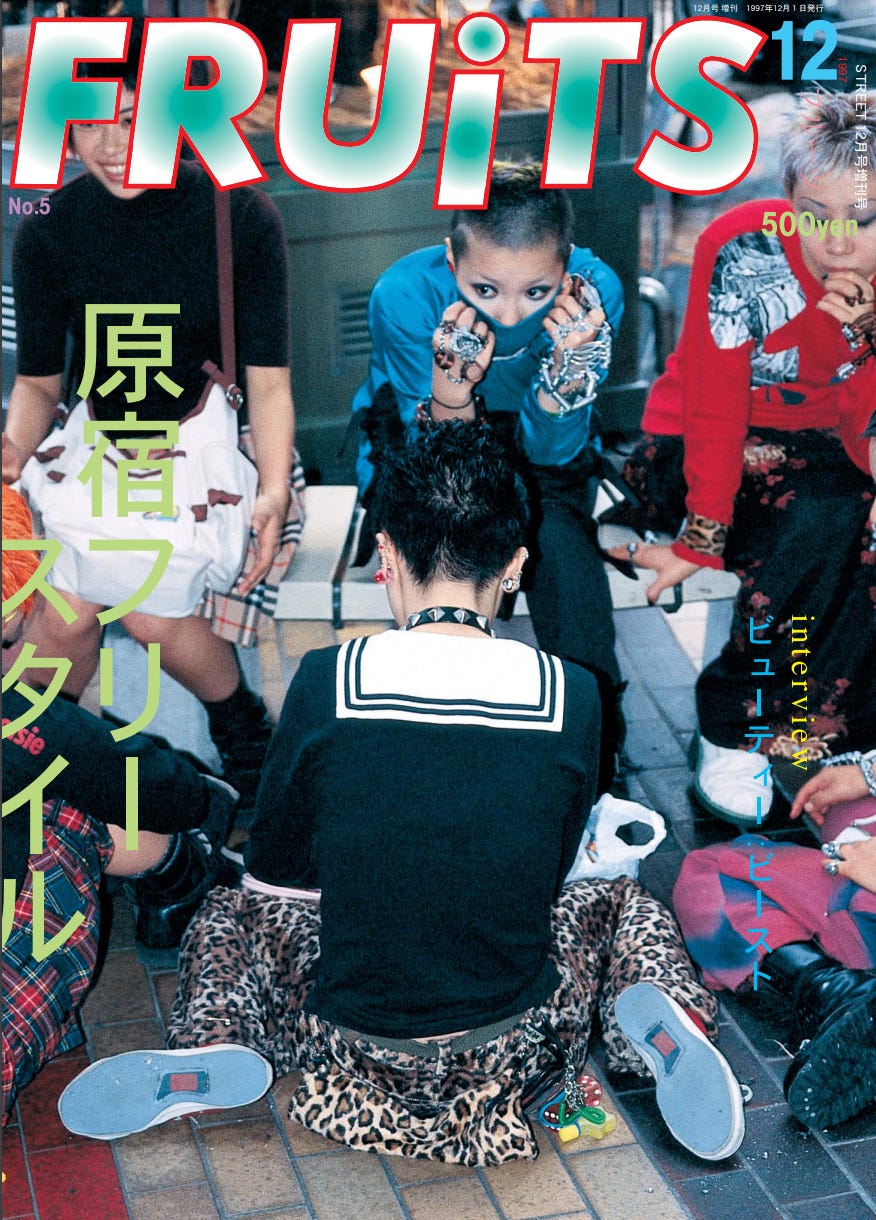

For this inaugural post, I wanted to begin with a publication that holds a deeply personal connection for me: FRUiTS Magazine. My relationship with it goes way back to around 2008, when I first stumbled across Daisuki Magazine.

For context, Daisuki was the first shōjo manga anthology published outside of Asia. It was a monthly magazine featuring serialized manga for girls, and I was completely captivated by it. I devoured the stories and obsessed over the beautiful illustrations, begging my parents for every new issue I could get my hands on.

But it wasn’t just the manga that stuck with me. In the middle of each issue, there was a small section about Japanese culture. It was there that I encountered my first kanji, learned my first Japanese phrases, and read about a neighborhood in Tokyo called Harajuku.

The fashion these girls and boys depicted in the magazine wore was dreamlike — a 1990s fairytale. Their self-expression was so bold and creative that it felt more like art than clothing. I was desperate to learn more, but at the time, the only information I could find on the German market was about cosplay, which clearly wasn’t the same thing.

From that moment on, one of my biggest dreams became visiting Harajuku to see this magical place for myself.

Fast forward a few years to my Tumblr-obsessed teenage phase, and that’s when I finally discovered what I had been searching for all along: FRUiTS Magazine.

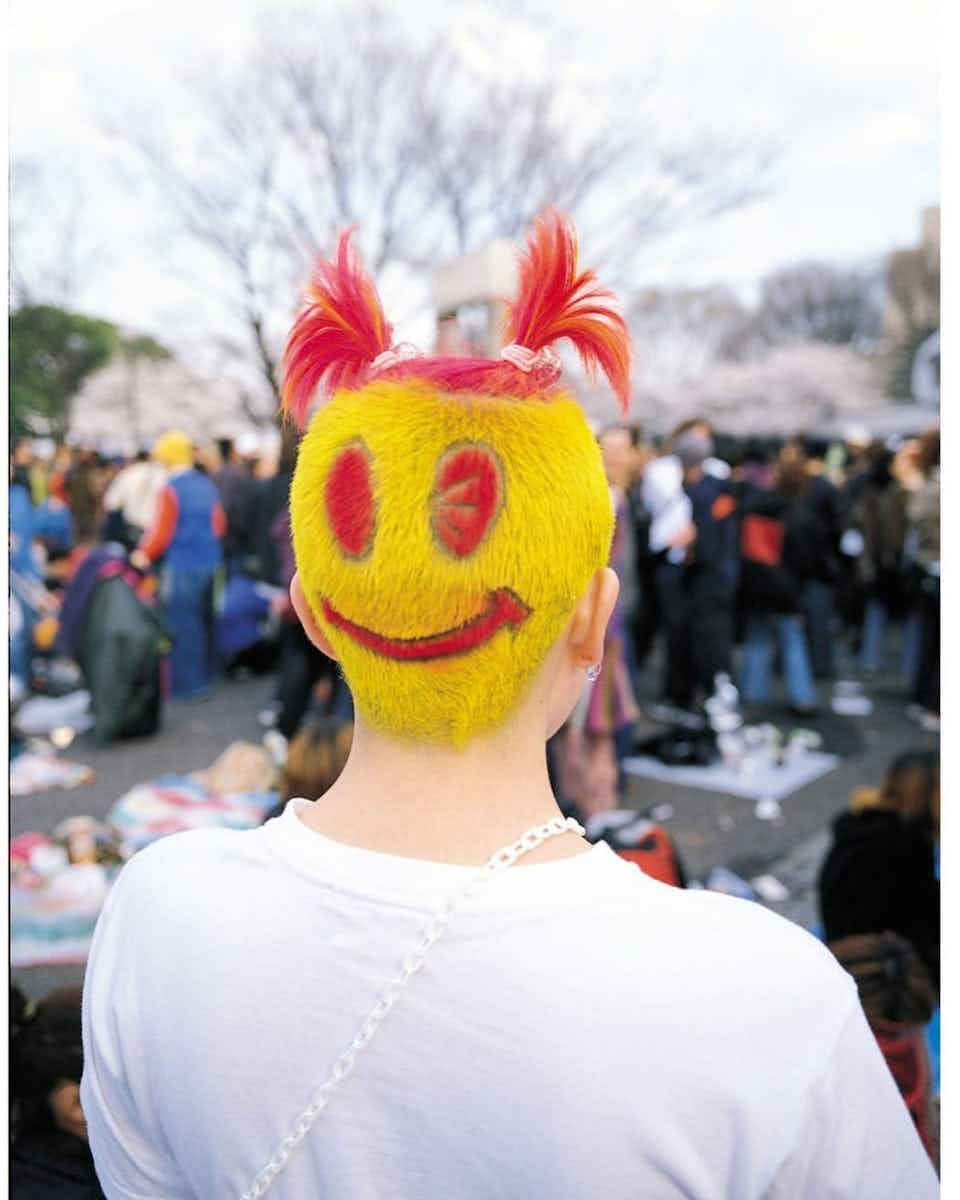

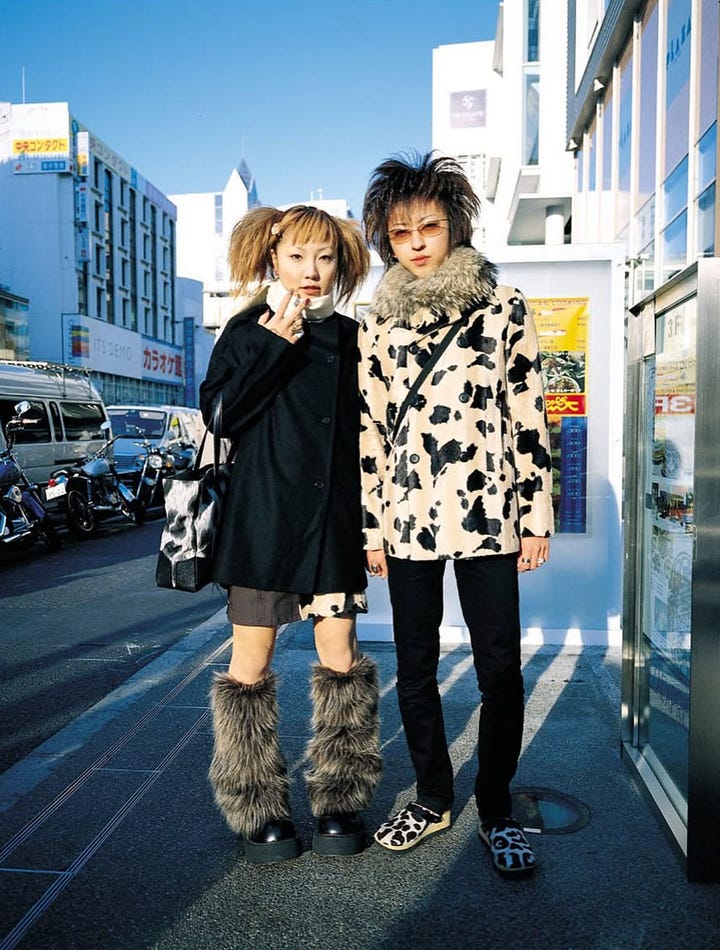

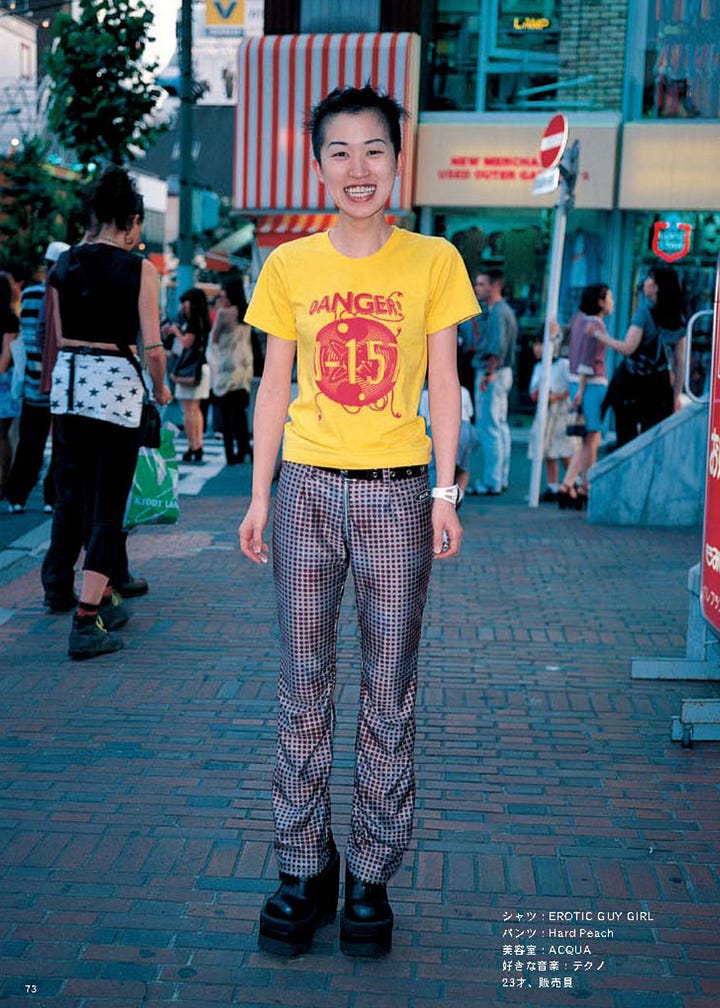

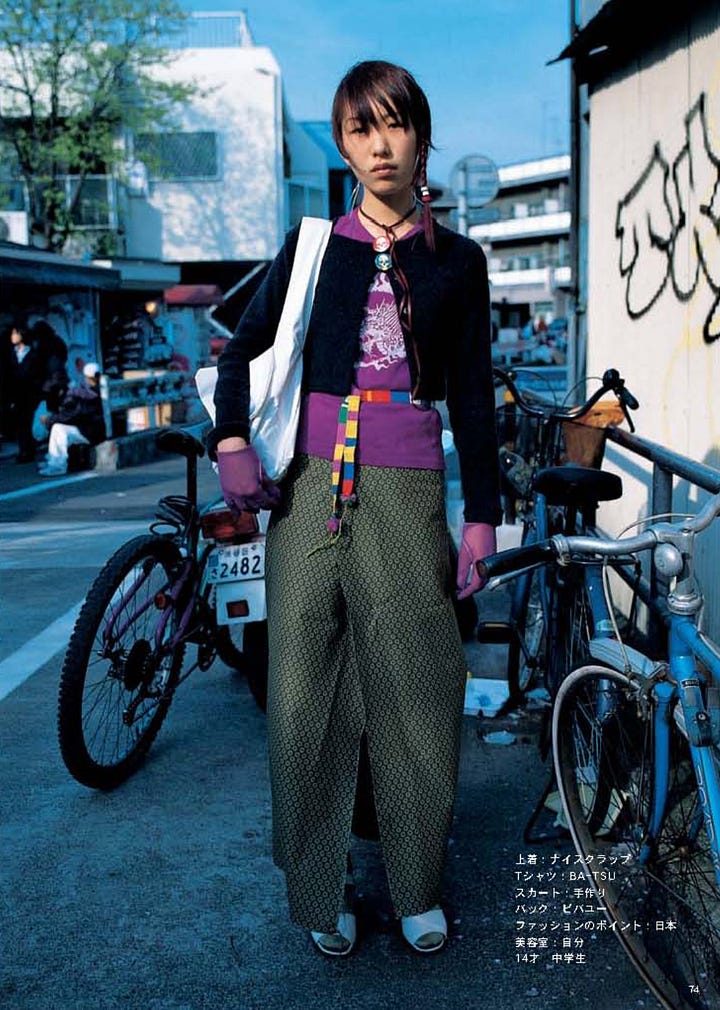

FRUiTS was everything I had imagined and more. A publication filled with street-style photography straight from Harajuku, it documented what people in the neighborhood were wearing with a level of authenticity and creativity that was unmatched.

FRUiTS?

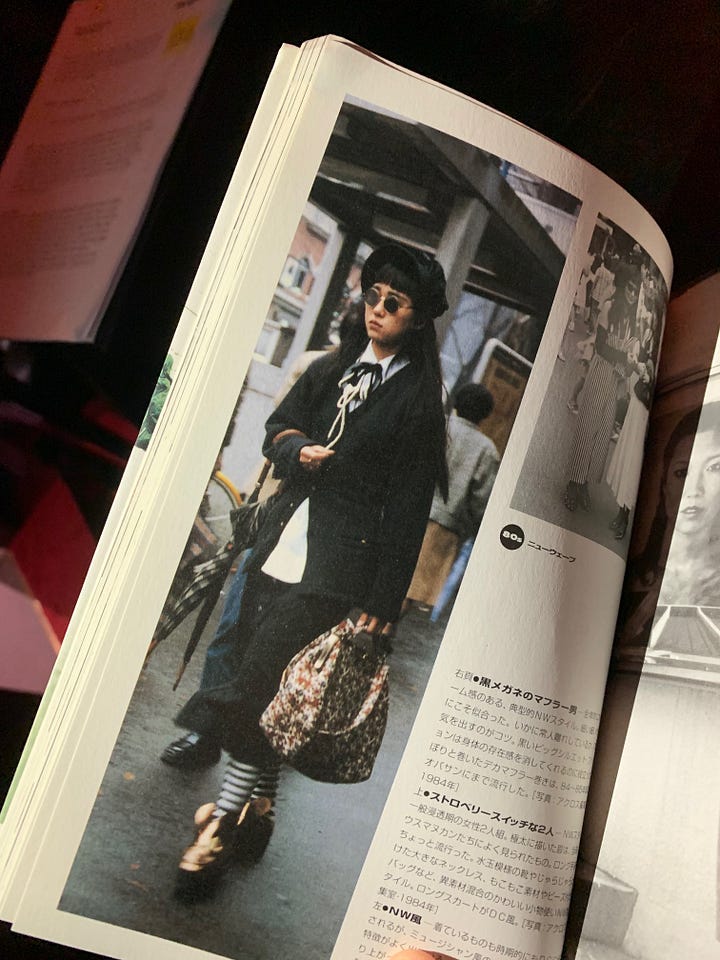

FRUiTS Magazine was founded in 1997 by Shoichi Aoki, a Japanese photographer and former programmer with a passion for street style. Before FRUiTS, Aoki had spent six months traveling through Europe, where he became fascinated by how people in different cities expressed themselves through fashion. This experience inspired him to create STREET Magazine in 1985, which focused on documenting the street style of London, Paris, and other European cities, including Berlin.

Upon returning to Japan, Aoki was struck by the burgeoning fashion scene in Harajuku, a neighborhood in Tokyo. The vibrant, experimental styles he saw on the streets of Harajuku were unlike anything he had documented in STREET Magazine. Recognizing that this unique aesthetic needed its own platform, Aoki founded FRUiTS Magazine, which centered exclusively on the neighborhood's groundbreaking street style.

The name "FRUiTS" was inspired by the fresh, colorful, and eclectic styles he observed—reminding him of fresh fruit, free from toxins and bursting with sweetness. Aoki described the fashion as playful, full of life, and almost “vegan-friendly” in its natural, unpretentious creativity.

Aoki’s Process

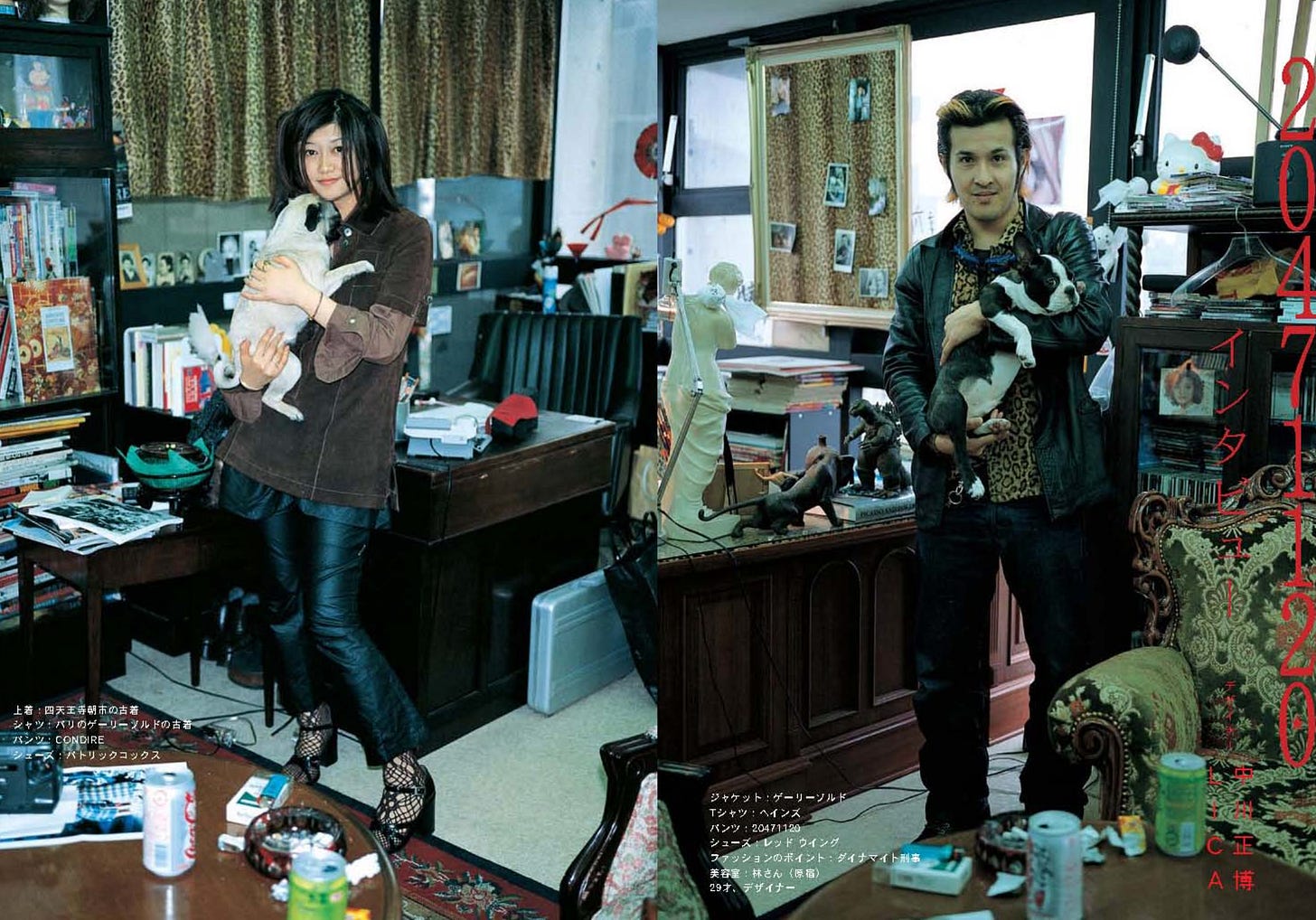

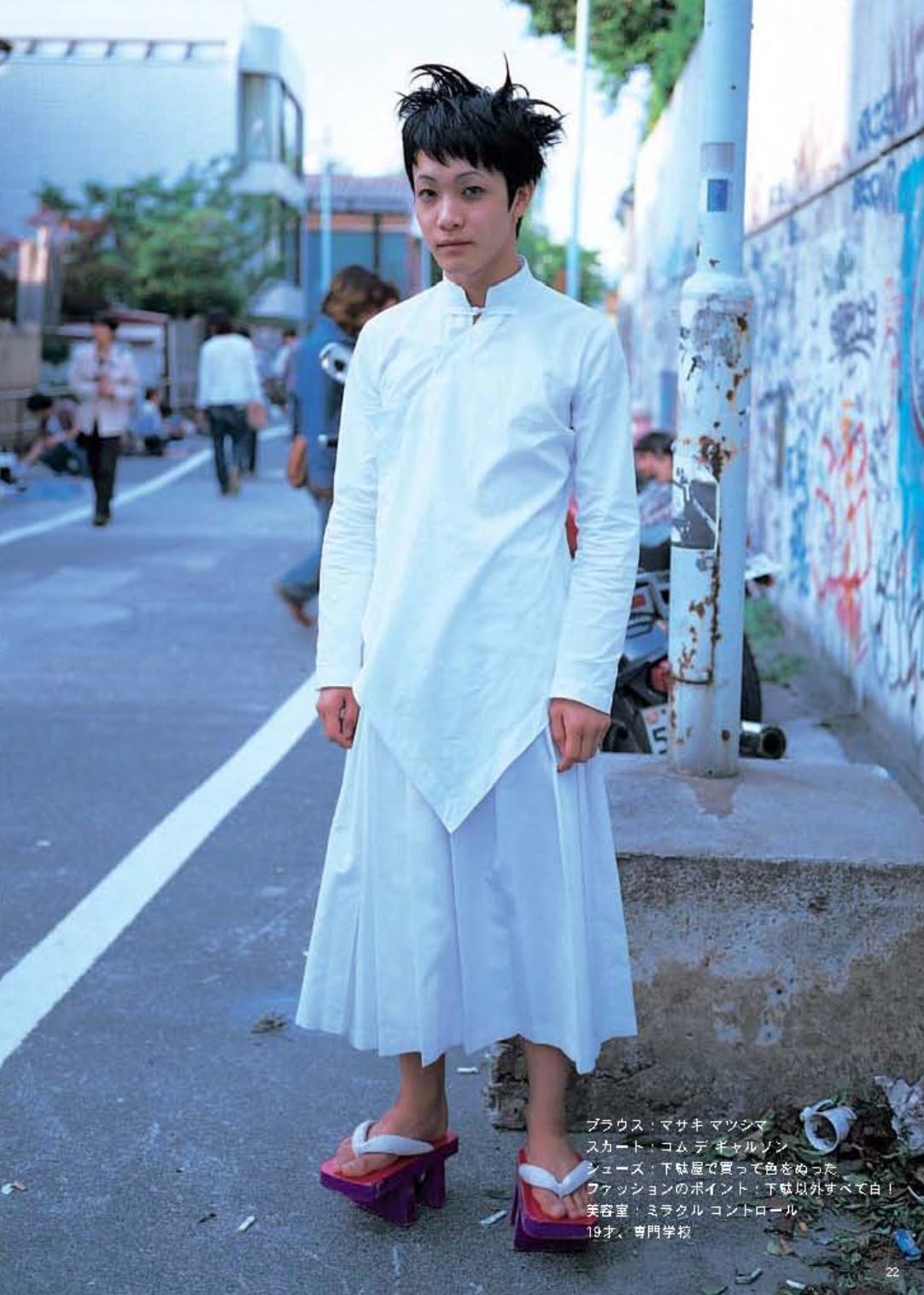

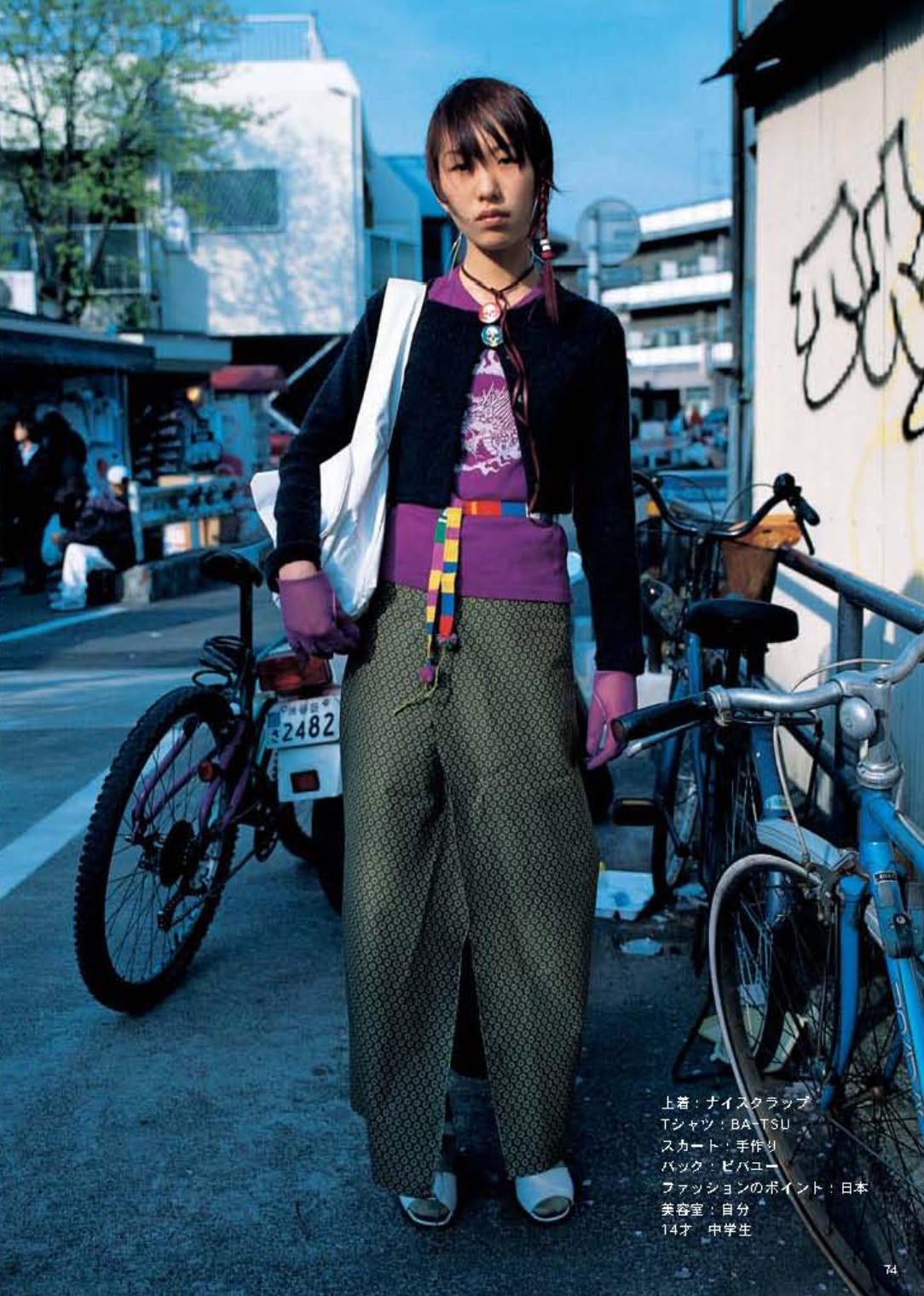

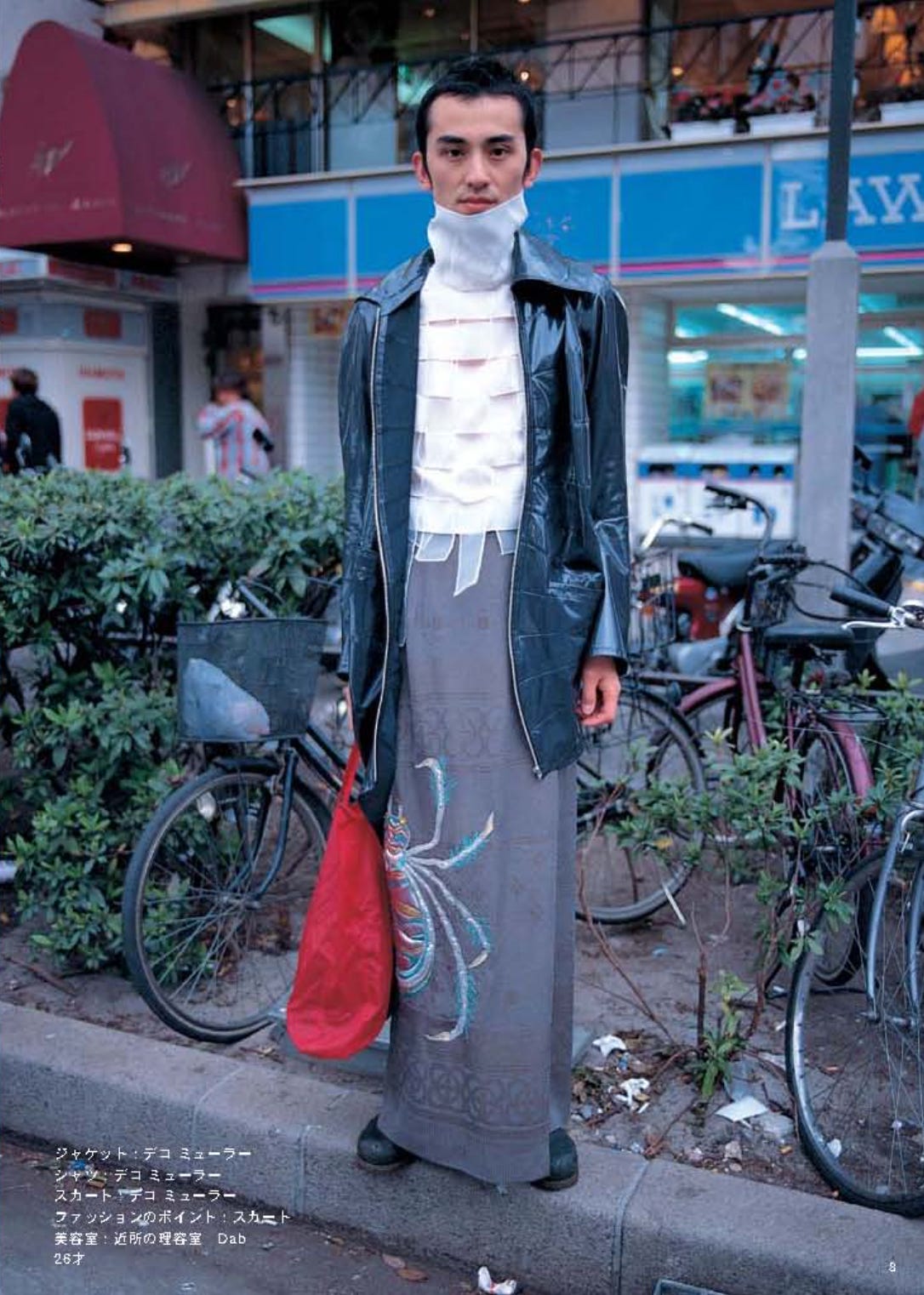

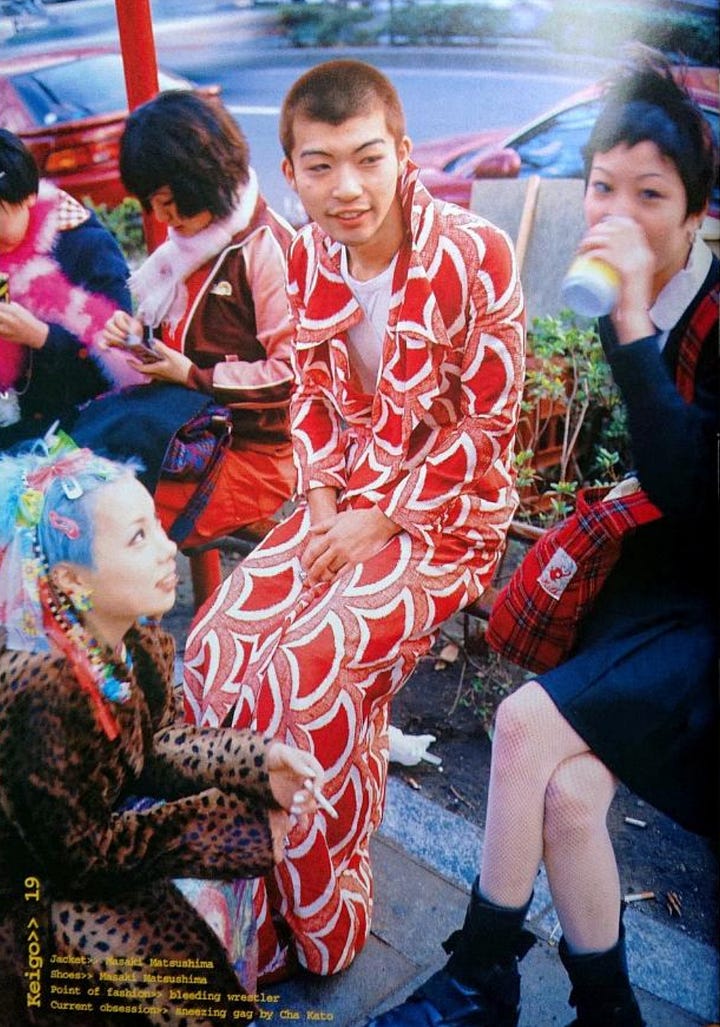

Aoki’s office was based in Harajuku, allowing him to step out multiple times a day to capture the most strikingly dressed individuals on the streets. His approach was straightforward: candid, full-length portraits of mostly young people in their natural surroundings. Alongside the photographs, subjects filled out questionnaires detailing their outfits—where the pieces came from, their attitude toward fashion, and any personal touches.

Some entries were highly detailed, listing every single item's origin—a treasure trove for modern-day reference and brands to look out for on reselling platforms. Others were more casual, with responses like, “Shirt: my boyfriend’s closet” or “Bag: from my mom.” These responses highlighted that Harajuku fashion wasn’t about designer labels or brands; it was about creativity, styling, and self-expression.

The Philosophy of Preservation

Aoki’s photography intentionally avoided embellishment. He saw himself not as a creator, but as a documentarian, letting the creativity of his subjects shine without interference. “Like sculptures in a gallery” was how Aoki described his subjects—artworks of the moment, created by the people wearing them. His goal was preservation: capturing these fleeting yet artistic expressions of individuality for future generations to see and appreciate.

Rather than styling or directing his subjects, Aoki’s influence was limited to choosing and categorizing them. He considered himself a “streetwear collector,” committed to archiving these ephemeral creations. For Aoki, fashion wasn’t about high-end labels or runways—it was about real people and how they wore real clothes in everyday life.

Integrity Over Commercialism

In the early days of FRUiTS, advertising agencies often approached Aoki, hoping to have their products featured in the magazine. He declined, adamant that FRUiTS remain a pure documentation of Harajuku street style rather than a commercial enterprise. For Aoki, FRUiTS was more than a magazine; it was an archive, a historical record of subculture, and a love letter to the artistry of the everyday fashion.

Harajuku District

Before diving deeper into the style and fashion of Harajuku, it's important to understand the context of where this phenomenon unfolded—and how the unique character of the place influenced it.

Tokyo is a city of distinct neighborhoods, each with its own flavor: Ginza’s polished luxury, Shibuya’s bustling commercial energy, Aoyama’s sophisticated minimalism, and Naka-Meguro’s trendy charm. Among them, Harajuku stands out as the rich breeding ground for some of the most exciting evolutions in fashion.

Harajuku doesn’t have strict geographical borders. Officially, it’s part of the Jingūmae district in Shibuya-ku, but its identity extends beyond administrative lines. Harajuku encompasses landmarks like the old Harajuku Station, the bustling shopping street Takeshita-dōri, the upscale Omotesandō boulevard, and iconic department stores such as Laforet.

Western Influence

Harajuku’s transformation into a cultural hub began in the post-war period when the area was rebuilt as an American military base for soldiers and their families. This influx of foreign residents brought imported goods and a sense of Western influence, which, combined with low rents and the introduction of car-free Sundays in 1977, created a magnet for young people. By the 1970s, Harajuku was known as a gathering place for youth culture—a reputation it would cement in the decades to come.

The area also benefited from its proximity to creative institutions like Nippon Beauty Academy, Vantan Design Institute, and Bunka Fashion College, which drew students eager to explore and experiment with their personal style.

The Birth of Harajuku Style

According to Shoichi Aoki, the founder of FRUiTS Magazine, Harajuku’s distinct identity began to take shape around 1996. This was when young people started taking their style into their own hands, breaking free from the cycle of trends dictated by designers, brands, and magazines. At the time, fashion was still largely top-down; individuals weren’t seen as drivers of style or self-expression. Harajuku flipped this narrative. What emerged was something more democratic and deeply personal: real people leading fashion, not just following it.

Much of this creativity played out in the Hokousha Tengoku—commonly referred to as "Hokoten," or "pedestrian paradise." With traffic cleared from the streets, young people, artists, dancers, and musicians were free to gather and showcase their individual styles. Hokoten became a vibrant stage for experimentation, a space where onlookers could observe, absorb, and be inspired. It fostered a feedback loop of creativity: young people brought bold new ideas, experimented for a couple of years, and then moved on, leaving space for the next generation to reinvent Harajuku anew.

In this way, Harajuku became a "third space" (a sociological term describing social environments outside of home and work) for Tokyo’s youth. It was a safe space for creative exploration and self-expression—an incubator for fashion subcultures. The dynamic relationship between the place and its people was symbiotic: Harajuku provided the space for these youth-driven movements to flourish, and in return, its inhabitants cemented Harajuku’s status as one of the most innovative and iconic districts in fashion history.

The Decline of Hokoten

This creative golden age began to wane in the late 90ies, when the pedestrian paradise was shut down, and cars returned to the streets. While Harajuku didn’t lose its magic overnight, this marked the beginning of its gradual decline as a hub for free, uninhibited self-expression. The loss of Hokoten is a reminder of how crucial third spaces are for fostering subcultures. These fragile ecosystems rely on environments where participants can both see and be seen, creating a fertile ground for creativity and community.

Even so, the legacy of Harajuku lives on. Its youth made it what it was: a place where fashion was loud, unapologetic, and deeply personal—a form of self-expression that was celebrated rather than judged. Visitors from around the world still flock to Harajuku, hoping to catch a glimpse of the characters immortalized in FRUiTS Magazine.

Harajuku’s Global Influence

Harajuku's influence extends far beyond Tokyo. It helped shape perceptions of Japanese fashion on the global stage, building on the success of the DC Brand boom and Japanese designers like Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo, who made waves in Paris. Recognition from Western fashion capitals like Paris, Milan, and New York elevated Tokyo as a serious fashion city. Harajuku, with its grassroots creativity, became the symbolic heart of this movement—a place where street style met high art, and where fashion was, above all, real and alive.

Harajuku Style

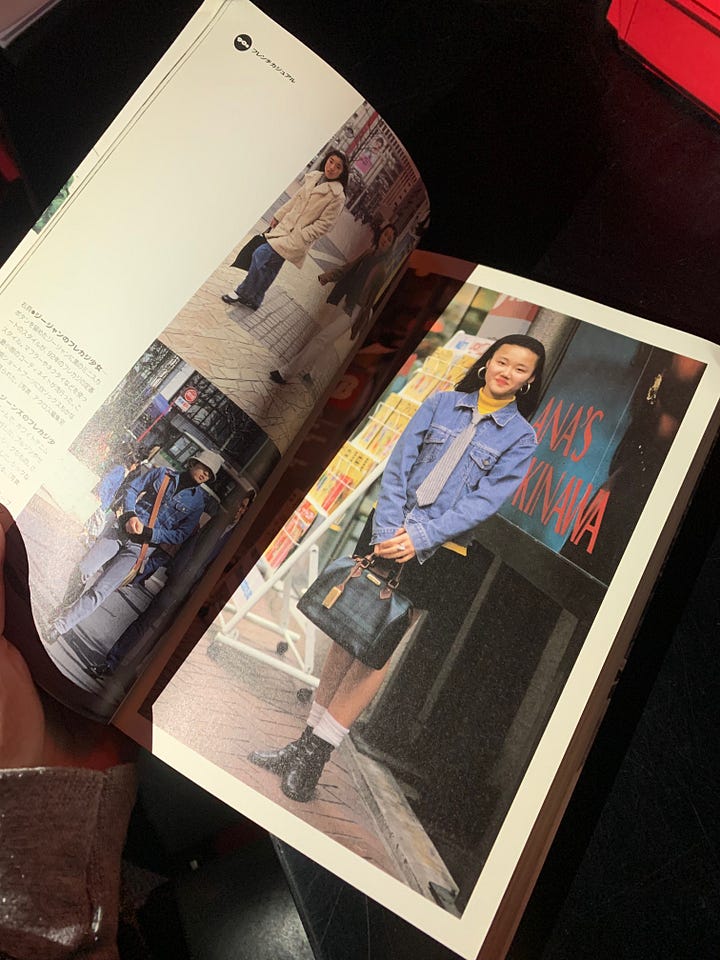

What made Harajuku style so unique compared to other street styles around the world, especially in the '90s? Its origins can be traced back to the 1970s, when creatives began flocking to Harajuku, drawn by the area's low rents and vibrant atmosphere. These trendsetters often traveled abroad and brought back inspiration from fashion hubs like London and Paris, introducing Japanese youth to global styles that they might not otherwise have encountered. The result was an exciting mix of influences that merged with Japan’s own cultural elements.

A particularly telling anecdote from that time speaks to Harajuku's appeal: someone recalled a manual on "How to Succeed in the Fashion Business," which advised aspiring creatives to move to Harajuku, rent a small, cheap room, set up an atelier, and start working. The neighborhood became a magnet for small fashion labels that seamlessly wove themselves into the area's culture.

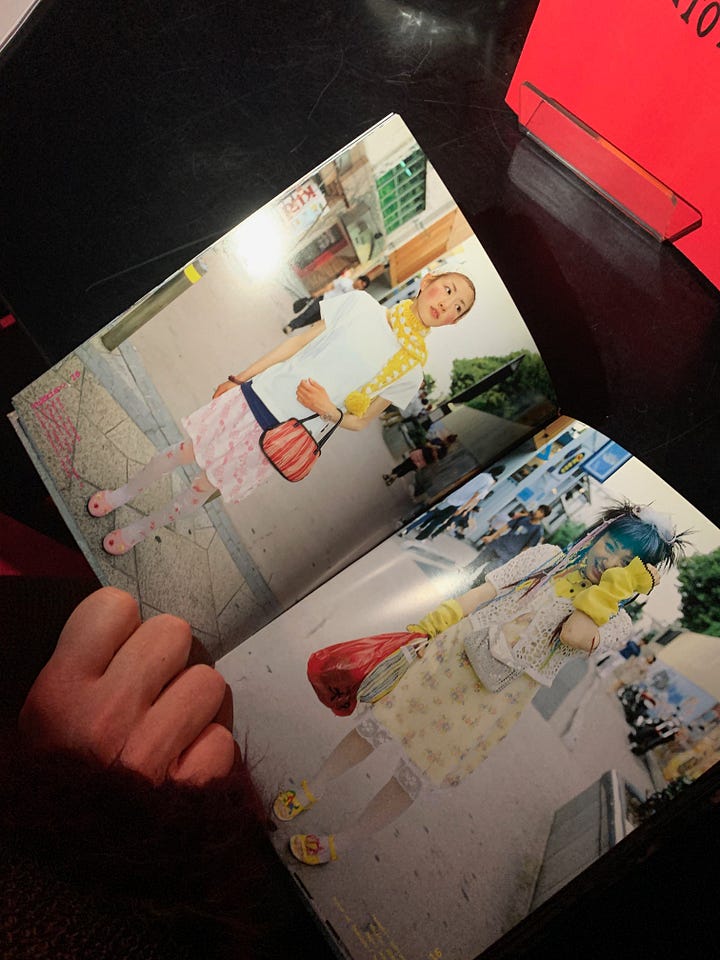

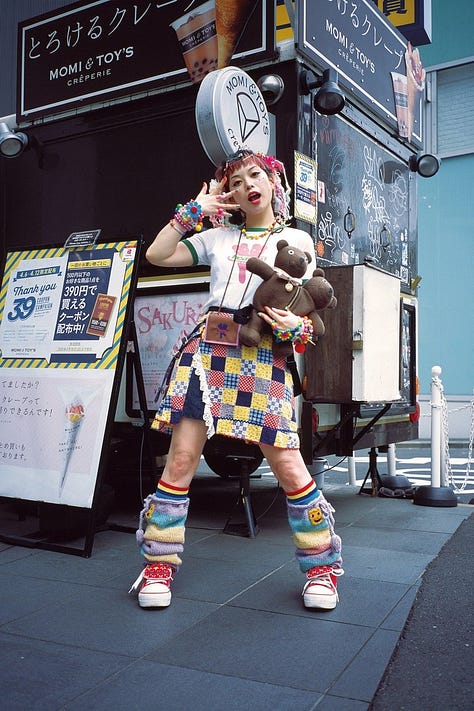

But Harajuku style wasn’t just about wearing the latest trends or even supporting local labels. It was about how people wore their clothes and how they styled them. Youth in Harajuku pulled together outfits from everything at their disposal—mixing traditional Japanese garments like kimonos with secondhand Western pieces, thrift store finds, or even hand-me-downs from family members. What mattered wasn’t what they wore but how they wore it. This creative freedom gave rise to many subcultures over the years, such as Kawaii, Decora, and even the so-called Fushigi-chan ("mystery kids")—individuals with styles so outlandish they defied categorization. Some people even changed into their eccentric outfits at Harajuku Station, transitioning from more conventional looks to full-blown self-expression once they arrived.

It’s important to note that Harajuku style was never cosplay. Shoichi Aoki, made a clear distinction between the two. While cosplayers were present in Harajuku, Aoki deliberately avoided photographing them, as he believed cosplay was about replicating characters, whereas Harajuku fashion was about creating something uniquely personal. He also rarely photographed Lolita styles, as he often found them overly derivative and unauthentic. Harajuku style wasn’t about trends, aesthetics, or fitting into a predefined category—it was about individuality. And as Aoki pointed out, true personal style is timeless and a skill in itself.

One of Harajuku style’s key influences was the iconic designer Vivienne Westwood. In the late '80s, her punk attitude and DIY spirit resonated deeply with Harajuku's creative community. They took her rebellious ethos and ran with it, pushing it further into the realms of the bizarre, kitschy, colorful, and eccentric. This creative chaos became a defining characteristic of Harajuku style, one that still inspires fashion generations today.

Harajuku wasn’t just a neighborhood—it was a canvas. It provided the space for young people to experiment, innovate, and express themselves, and their bold creations continue to capture imaginations worldwide.

Pushing Trends

Even back then, Shoichi Aoki noted that fashion in Harajuku changed roughly every three months. It was an ever-evolving cycle, not unlike the microtrends we grapple with today—but at a slower, more deliberate pace. There were always those young pioneers—the ones boldly experimenting and perfecting new styles—until others inevitably picked up on their ideas. And, of course, that was the moment the innovators moved on, bored by the very thing they’d started. For them, being part of a trend wasn’t the point; it was about staying ahead, constantly pushing boundaries. Harajuku's fashion scene acted like an evolutionary system: organic, cyclical, and self-renewing.

Interestingly, Aoki observed that the true pioneers often looked slightly uncool at first. And that’s an important lesson in trends: if you want to push boundaries in fashion, you sometimes have to risk looking awkward or offbeat in the beginning. Confidence in your vision makes all the difference. At FRUiTS Magazine, Aoki would often tell his team not to bother photographing someone just because they looked universally "stylish." The magazine was never about capturing polished perfection—it was about not missing the ones who were taking risks.

Beyond documentation, FRUiTS Magazine served as a launchpad for new talent. Securing a coveted spot in its pages could generate enough buzz to help young creatives break into the fashion industry. It became a platform that celebrated not just individuality, but the courage it takes to set trends rather than follow them.

End of an Era

As mentioned earlier, Harajuku began to change irreversibly once cars were allowed back into the neighborhood. Like Camden in London, it slowly morphed into a souvenir-saturated tourist trap, where spotting the creative locals who had once made the area so iconic became increasingly rare. When I first visited Tokyo in 2019, Harajuku was at the top of my list. Jet-lagged and wide awake at 6 a.m., I ventured there deliberately early to see the streets empty. I knew that the Harajuku I had dreamed about—the one immortalized in FRUiTS—was a thing of the past, but I wanted to imagine what it must have felt like during its heyday in the mid-1990s.

Later that week, I returned to the neighborhood, now crowded with tourists. It was hard not to feel disappointed. The vibrant, eccentric culture I had idolized was nowhere to be found. That said, Tokyo itself didn’t let me down—elsewhere in the city, I found individuals whose style was still leagues ahead of anything I was used to in Europe.

Shoichi Aoki himself observed a decline in Harajuku’s fashion scene by the 2010s, which he attributed largely to the rise of fast fashion. Many people stopped curating their looks with creativity and began wearing single-brand outfits, head to toe—something that felt inauthentic, almost as if they were brand ambassadors (though they rarely were). This shift led to Aoki’s famous decision to stop publishing FRUiTS Magazine in 2017, citing that there simply weren’t enough interesting people to photograph anymore.

The rise of social media also played a role. Harajuku’s young trendsetters no longer needed the magazine to amplify their style; platforms like Instagram gave them a direct line to an international audience. Why wait for a chance encounter with a photographer when you could self-curate and reach thousands online? Similarly, younger generations stopped buying magazines, preferring to follow influencers whose style felt more personal and immediate.

Adding to the erosion of Harajuku’s authenticity were superficial appropriations of the culture by Western celebrities. Gwen Stefani’s “Harajuku Lovers” line, for example, was widely criticized for its exploitative and surface-level aesthetic, stripping away the creativity and depth of the original subculture. Avril Lavigne’s nods to Harajuku culture followed a similarly shallow path. These gestures, while commercially successful, misrepresented a vibrant and highly creative movement, reducing it to a mere aesthetic.

Meanwhile, the independent designer stores and ateliers that had defined Harajuku’s charm were slowly replaced by multinational chains like H&M and Zara. These globally ubiquitous brands brought homogeneity to a place once renowned for its individuality. Today, Harajuku is just another major city high street, profiting off a subculture that it no longer truly represents.

The loss of Harajuku as it once was feels like the end of an era—a reminder of how fragile and fleeting youth subcultures can be without the spaces and conditions that allow them to thrive.

FRUiTS Magazine Is Dead, Long Live FRUiTS Magazine

Even after the magazine’s discontinuation, FRUiTS Magazine continues to leave its mark on the fashion world. Its influence is felt across generations of creatives, with many designers and stylists collecting back issues as valuable reference material. On social media, the magazine’s legacy lives on as its archives are slowly uploaded to Instagram, allowing a new audience to discover the vibrant subculture it captured.

Recently, brands and collaborators have paid tribute to the magazine in various ways, celebrating its enduring cultural significance. Here are some notable examples:

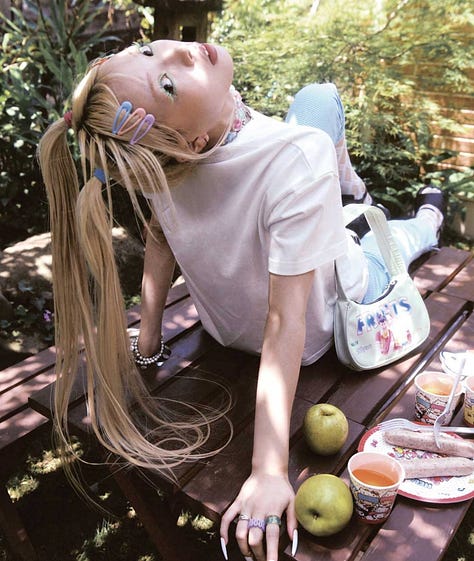

THE FACE

In a nod to FRUiTS Magazine’s iconic style, THE FACE ran a cover story featuring Beabadoobee, photographed by Shoichi Aoki in a classic FRUiTS spread. A fan of the magazine herself, Beabadoobee embraced the playful, eccentric aesthetic. The accompanying interview with Aoki hinted at a potential return of the magazine. “I, for one, would love to see FRUiTS in print again,” Aoki said, adding, “but it’s a case of thinking creatively and realistically about how this can happen in the digital age. It’s very much a case of ‘watch this space.’”

HEAVEN by Marc Jacobs

Marc Jacobs’ polysexual line, Heaven, launched in 2020 and is widely believed to draw inspiration from FRUiTS Magazine. Heaven focuses on early 2000s nostalgia—more specifically, the feeling of being a teenager in that era. Shoichi Aoki collaborated with the brand to shoot a lookbook in his signature style, blending Heaven’s designs with the unmistakable energy of Harajuku fashion. A true match made in heaven.

Opening Ceremony

When FRUiTS ceased publication in 2017, Opening Ceremony honored its legacy with a collection of graphic tees. The brand’s founders, long-time collectors of the magazine, wanted to bid farewell to the publication that had been a vital source of inspiration for them since the 1990s.

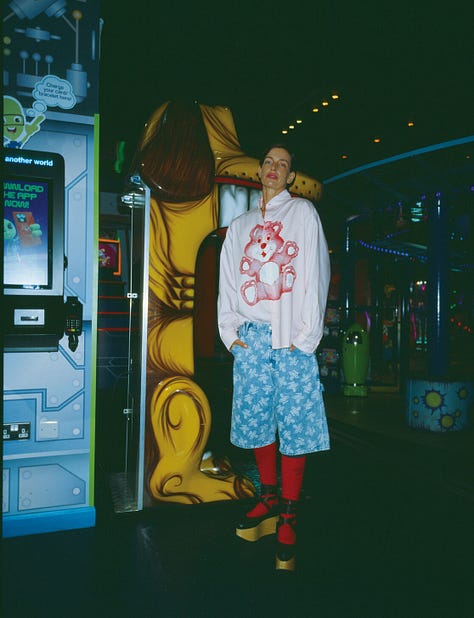

Praying

The label Praying teamed up with FRUiTS Magazine for a capsule collection featuring hoodies, T-shirts, and bags adorned with the magazine’s instantly recognizable logo. The incredibly fitting and colorful editorial for the collection, by GATA, embraced the magazine’s eccentric, bubbly styling of the 1990s, set against the nostalgic backdrop of a trailer park.

Palace x Vivienne Westwood

Recently, Shoichi Aoki captured the collaboration between skate brand Palace and iconic designer Vivienne Westwood. The editorial featured a fitting cast of musicians, activists, and models, blending Tokyo’s nostalgic FRUiTS-era aesthetic with the streets of Soho. Styled in pieces from the collection, the campaign culminated in a zine that celebrated Westwood’s foundational influence on Harajuku style and Palace’s subcultural roots.

The Enduring Legacy of FRUiTS

Japanese streetwear has since evolved—sleeker, more muted, streamlined in both color and construction, and increasingly intertwined with luxury brands. According to a 2017 study, Japan accounts for 30 to 40 percent of some global luxury brands' profitability. The vibrant, unrestrained days of FRUiTS may be a thing of the past, but it's clear that we wouldn’t have arrived at this moment without Shoichi Aoki's vision.

The archives of FRUiTS encapsulate more than just clothing—they embody the joy, freedom, and experimentation of youth. Often weird, niche, and wonderfully unconventional, the styles documented are compelling precisely because they defy the mainstream, celebrating individuality in its most raw and fearless form.

Harajuku teaches us a lasting lesson: true creativity isn’t always sleek or immediately understood. It thrives in risk, in discomfort, and in the audacity to look strange before the world catches up.

Though the pedestrian paradise has faded and FRUiTS is no longer in print, the spirit of Harajuku street style lives on—through fashion, through influence, and through the reminder that fashion, at its heart, is about people boldly wearing who they are.

I hope you enjoyed this deep dive into FRUiTS Magazine—a publication you’ve likely encountered before, whether directly or through the countless references it’s inspired. Despite its frequent nods in pop culture, the story behind it is rarely explored beyond the surface, even though it’s such an incredibly fascinating tale.

Let me know how you feel about this new format! Is there something in print you’ve been curious about and would like me to unpack in a future piece? If you enjoyed this and want more deep dives into art direction, fashion history, or creative storytelling, consider subscribing—I’d love to have you here.

Until next time, cheers!

Kimberly

The content I share on this Substack reflects my personal experiences, insights, and interpretations. Much of what I write draws from my own journey, along with research conducted through a variety of sources, including articles, books, exhibitions, and other creative outlets. While I strive to present accurate information and credit all sources to the best of my ability, my perspective and interpretation shape how this information is presented.

Please note that I cannot guarantee the absolute accuracy of everything stated, as the subjective nature of creative exploration always leaves room for interpretation. I aim to source beyond the most common channels, such as Pinterest, to bring you discoveries that might not surface from an algorithm. All images are used for educational purposes or to promote the original artists. Similarly, all imagery used is credited as thoroughly as possible, though unintentional omissions or errors may occur. All materials in this Newsletter belong to their copyright holders. If any credit needs updating or correction, please feel free to reach out, and I will promptly address it.

Thank you for your understanding and for joining me on this creative journey. 🌟

A little extra: I’m currently traveling, on my annual round of visiting family and friends in different countries over the holidays. I wrote most of this article on trains and in friends’ living rooms during some downtime. I always make sure to visit as many exhibitions and galleries as my schedule allows because you never know when you’ll stumble upon something truly special. Sometimes, you have to sit through a few uninspiring shows to find the ones that leave a lasting impression—ones you’ll think about for months or even years to come. Well, that’s exactly what happened to me last week.

While in Switzerland, my boyfriend and I stumbled upon a truly unique exhibition, which was a perfect replica of a Japanese bar, much like those found in Golden Gai, Shinjuku, Tokyo. The space was complete with Japanese books, magazines, and Japanese beer—all available for visitors to take for free. And one of the books on display? The FRUiTS Magazine Book. I couldn’t believe it. I asked to read the books, and they agreed, so not only did I get to dive deeper into my research for this article, but I also ended up giving a live version of this article to everyone present. It was magical.

(If you happen to be in Switzerland, feel free to DM me. I’m happy to share the exact location of the exhibition because you absolutely should go if you can.)